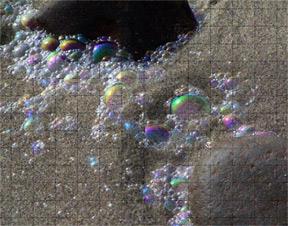

Foam is essentially many bubbles sticking together. However, seawater alone will not foam. If you take a jar of fresh or salt water and shake it vigorously, you will get some transient bubbles, but no foam. There is a missing essential ingredient - organic matter - which is necessary for foam formation. Organic molecules allow bubbles to stick to each other. These organic molecules come mostly from dead phytoplankton. The ocean surface has a thin film of active compounds (oils, fats, proteins, and others) about one micrometer thick called the nanolayer. The nanolayer is one part of a collection of thin layers traditionally referred to as the microlayer1, home to buoyant organics, particles, microorganisms, algae, fish eggs, and larvae and various life stages of other small animals. You can see the effects of this organic film on a calm ocean as a surface slick. Many of the organic molecules that contribute to foam are released from algae that have died and decayed. Air bubbles, formed in the turbulence of waves, collect these organics which change the water cohesion properties to let the bubbles stick together and make foam. All these bubbles in foam also burst, just as described above, releasing massive numbers of small droplets of seawater into the air, complete with both salts and organics. If you wear glasses and walk the beach on a stormy day, you will find that a greasy fog develops on your lenses which is difficult to clean off. This film is from the salts and organics contained in airborne ocean mist that collects on your glasses. The above picture illustrates this mist of droplets from churning waves and popping bubbles drifting over the south end of Netarts Bay. These drifting droplets carry sea salts and organic material into the atmosphere to be distributed by the prevailing winds. The water in the droplets evaporates, concentrating the salts into saturated solutions and finally crystals. These particles, called aerosols, often drift inland to be deposited on our ferrous metal tools and help them rust. It is estimated that 123 million tons of sea salt world wide is aerosolized each year. Sea salt aerosols not only contribute to corrosion problems but also, when drifting over cities, react with atmospheric pollutants such as nitric acid and affect people’s respiratory health2.