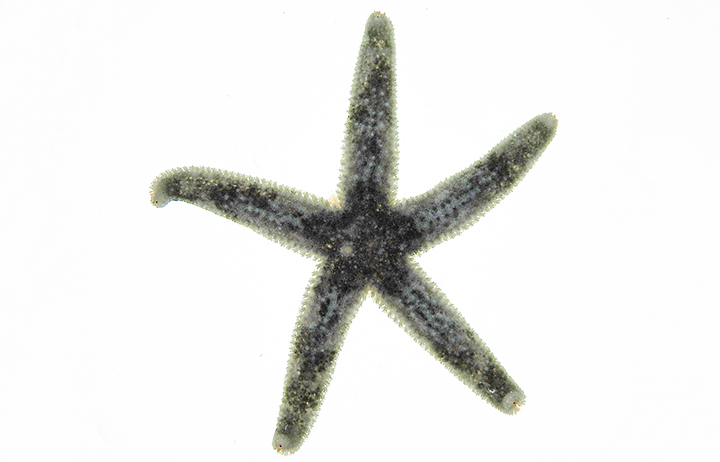

Pycnopodia helianthoides

Sunflower Star

Alaska to Mexico

Family Asteriidae

Native

With up to 26 arms, the Sunflower Star is the largest seastar on our coast, and one of the largest in the world, reaching a span of over three feet (one meter). It can be found near rocky tide pools and on sand and gravel inside Netarts Bay (see below). It is also most voracious and the speediest, moving up to more than two meters an hour.

The Sunflower Star is an opportunistic feeder and will act as either a predator or a scavenger. It seems to prefer dying or dead prey which are easier to get than live ones. It also an active sea star, so it has a large appetite. Besides bivalves, it eats barnacles, sand dollars, sea urchins, sea cucumbers, snails, dead fish, even dead birds. It also inverts its stomach to eat extraorally, but in addition, it will often swallow its prey whole. Large sunflower stars can excavate sediments and dig down to reach buried prey.

It can range in color from bright orange to solid purple, or as the one pictured here, multicolored. It can reproduce sexually by broadcast spawning or asexually by fragmentation, the splitting of the body either on purpose or by accident.

Around 2011-12, a severe disease, called the “sea star wasting disease”, hit all the seastars along the Pacific coast from Alaska to Mexico, in some areas wiping them out completely. A series of articles waswritten for our newsletter “Netarts Bay Today” regarding this devastating disease. The Sunflower Star was hit the hardest, and though once common locally, to my knowledge has not been found here since.