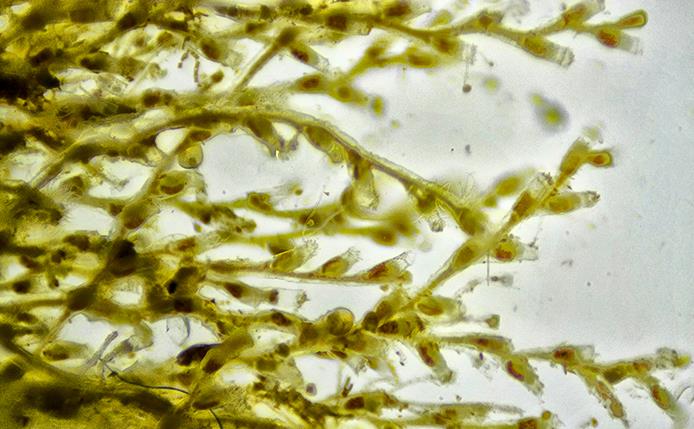

Utricia grebelnyi

Painted Anemone

Alaska to California

Family Actinidae

Native

This beautiful, but subtidal, anemone has a column that is usually striped and mottled with variable amounts of red and olive green and tenacles that have a center band of purple, rose, to sometimes yellow. The column is bumpy with tubercles. This is the anemone that I knew for decades as Tealia crasicornis, which is the name of a totally different looking European anemone. It was finally brought into the genus Urticina, then more recently given its current specific name. It is common near the bottom of the riprap that lines the northeastern edge of Netarts Bay.