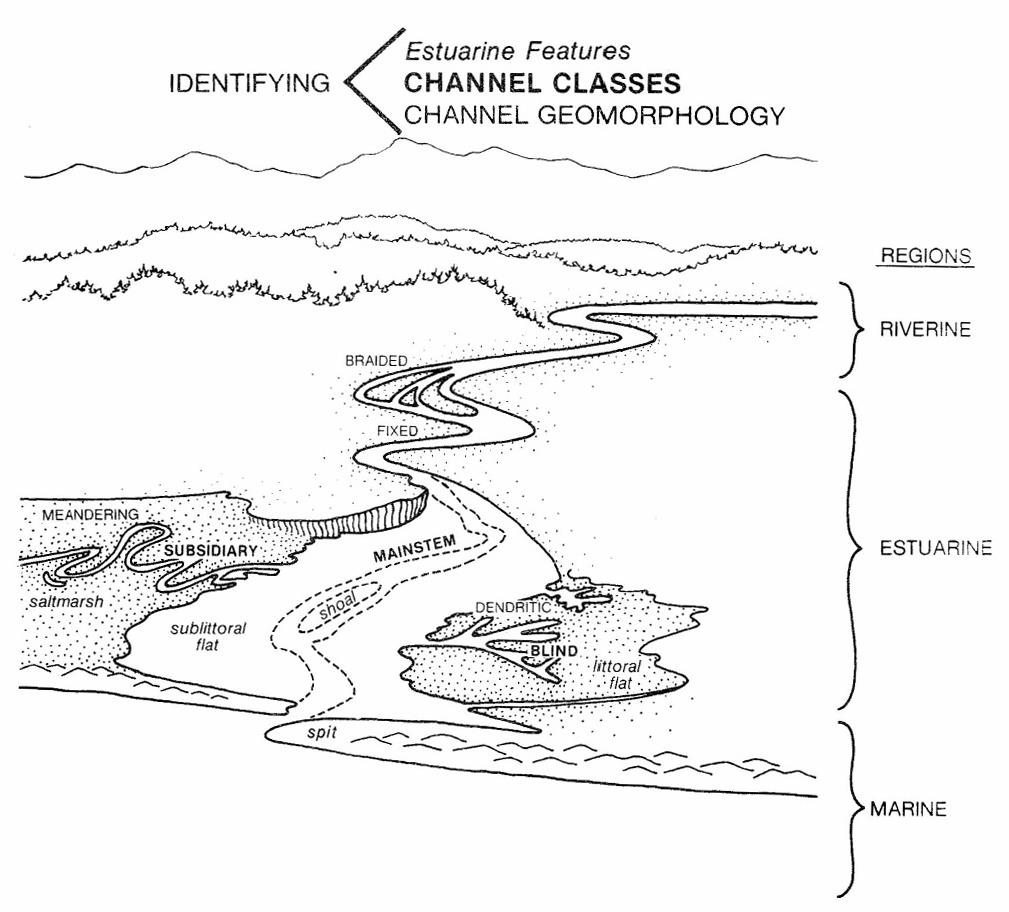

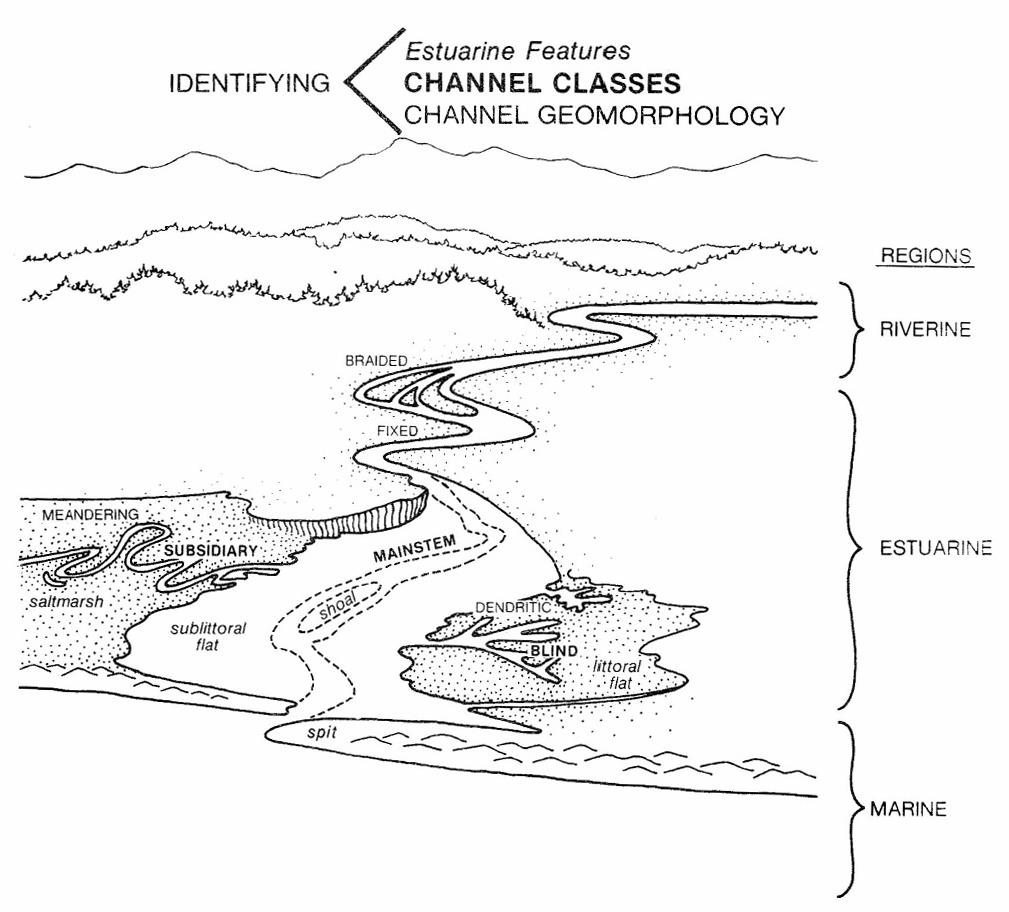

Channels, said Charles Simenstad, "form the estuary's circulatory system" (Simenstad, 1983). They are the conduits that link marine and riverine ecosystems, and they play a major role in the production of fisheries and wildlife. Unfortunately, this recognition is only recent. In the past, estuaries and their channels were exploited for agriculture, industry, and colonization. Many around the US and the world have been damaged or destroyed. We are lucky that Netarts Bay, a bar built estuary covering almost 3.5 square miles, along with its channels, remains mostly intact.

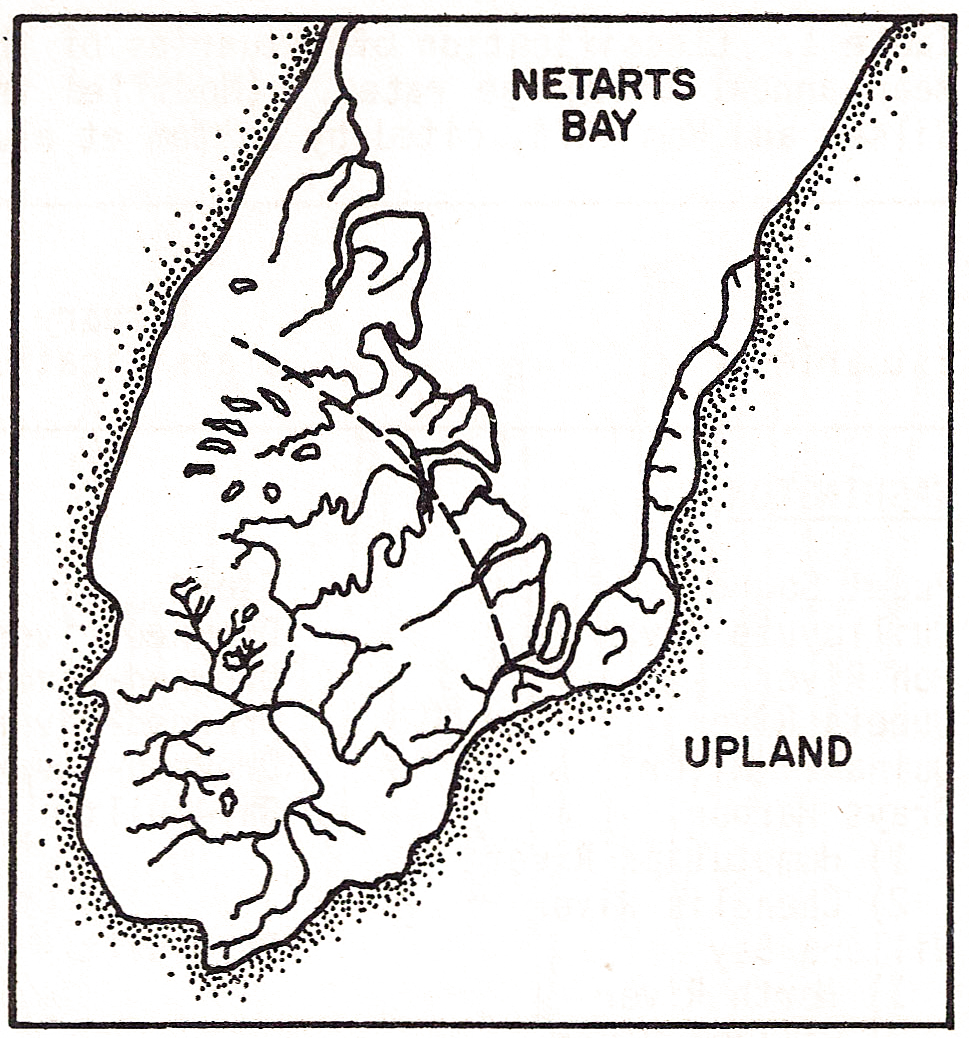

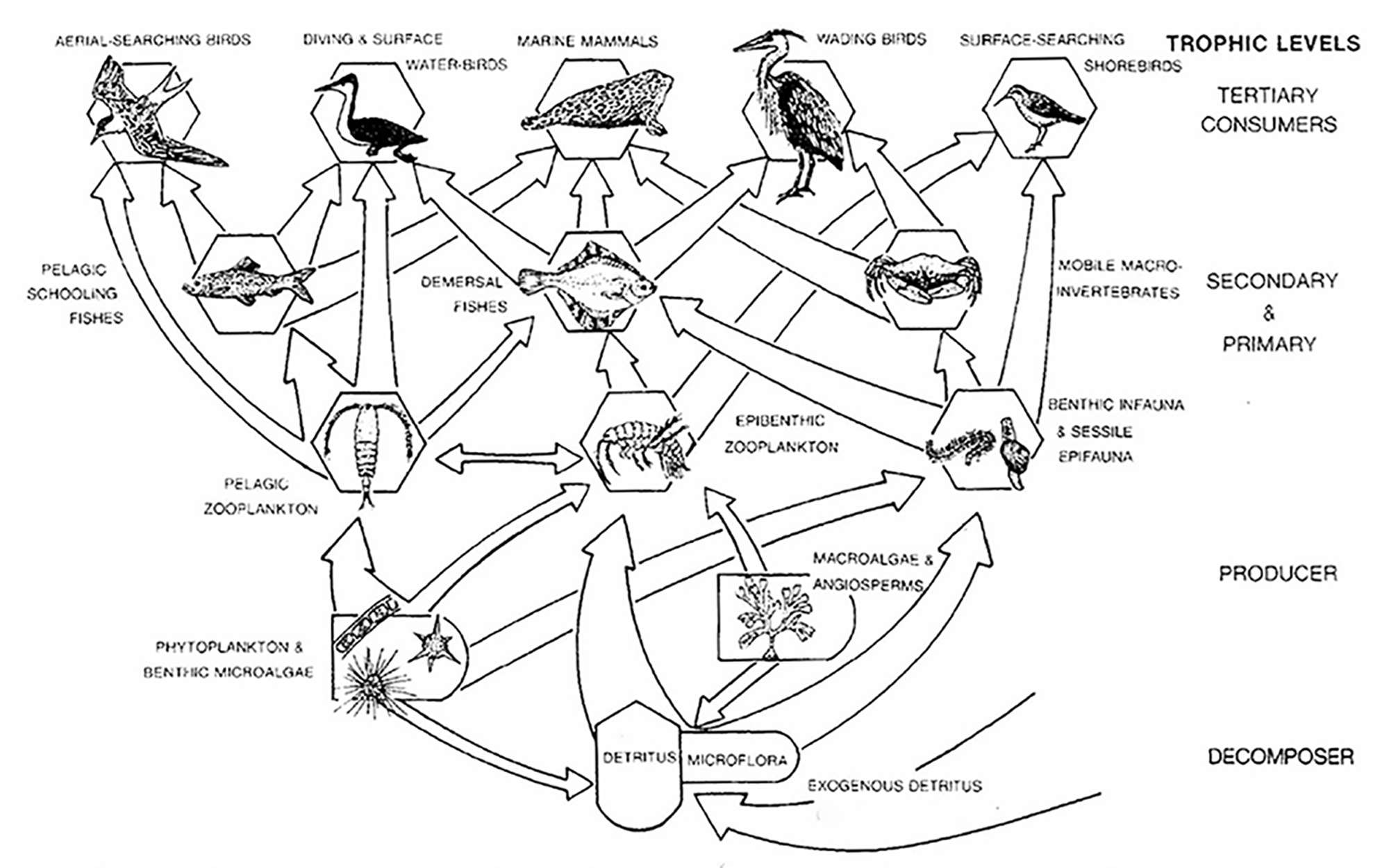

To the left is a diagram from Simenstad, 1983, of representative estuarine components. Although Netarts Bay has no river discharge of fresh water (Jackson Creek no longer flows into Netarts Bay), other features in the figure are similar to those evident in the photograph of the salt marsh at the beginning of this article. You can see in this image of the south end of the bay, the mainstream channels, the adjacent littoral flat (there are few sublittoral flats in this shallow bay), meandering subsidiary channels, and blind dendritic channels within the salt marsh habitat. In addition to this southern mature high marsh in the photo and the immature high and low sandy marshes along the west side of the bay that are mostly out of the photo, there are small pocket marshes with their own channels along Netarts Bay Road on the east side of the bay near the entrances of small freshwater streams. Yeager Creek is an example.

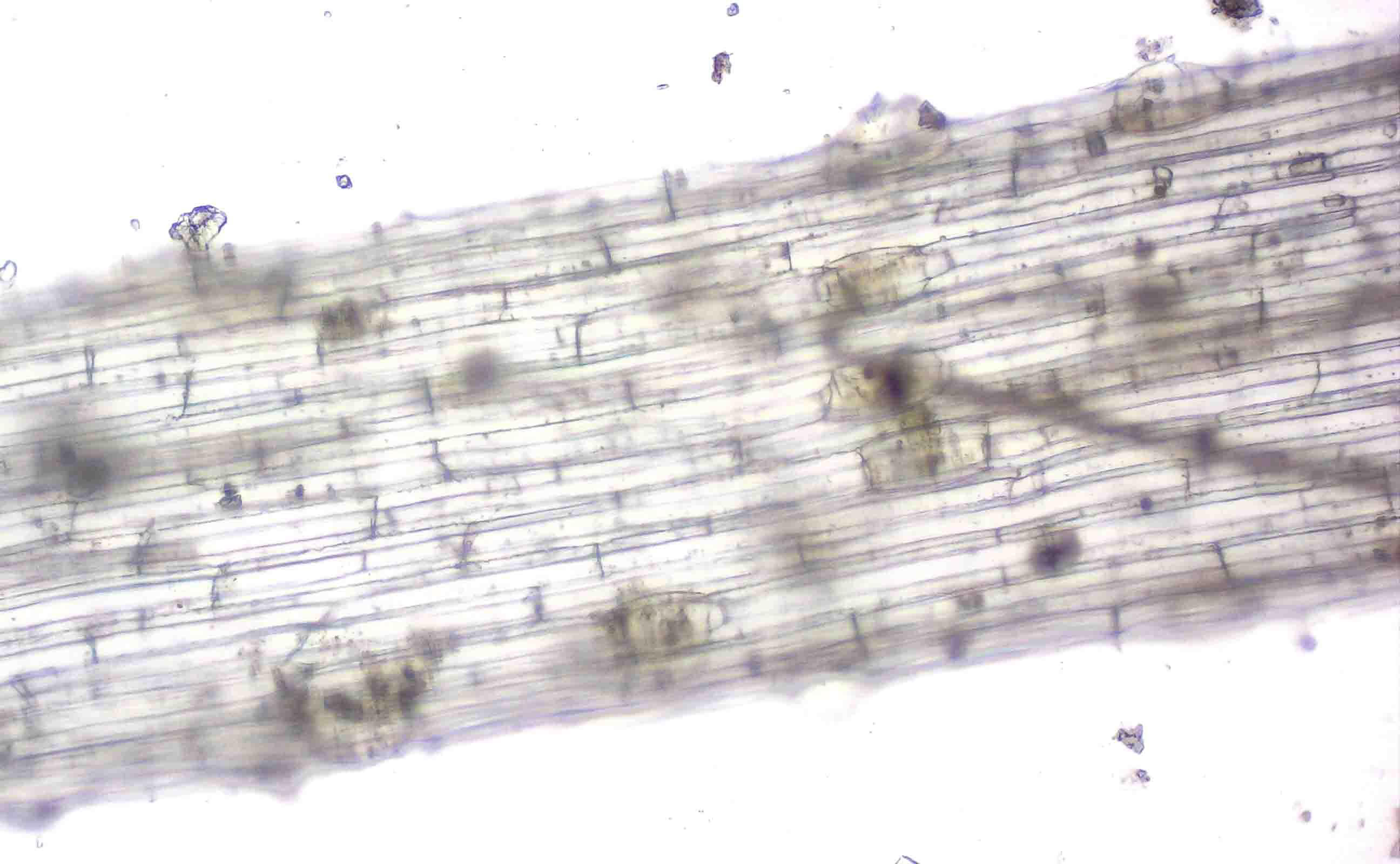

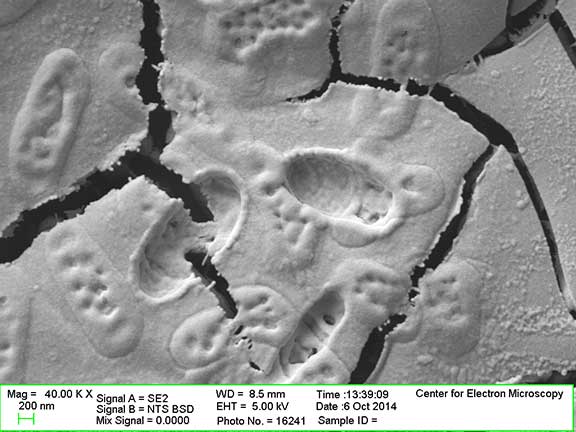

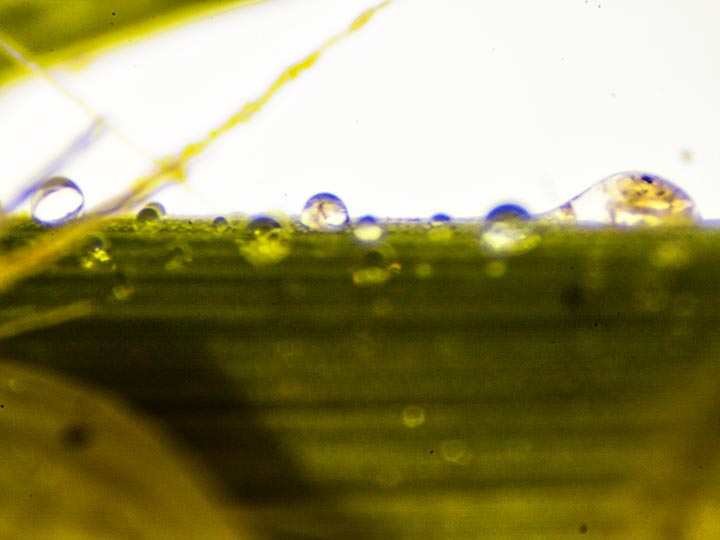

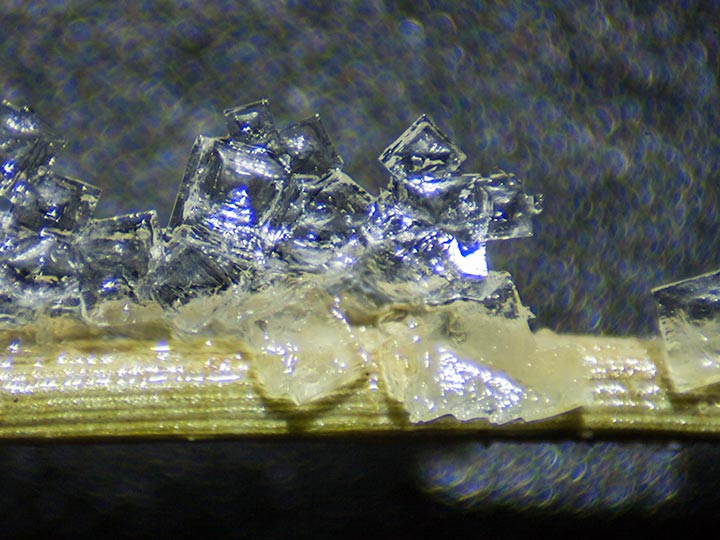

A typical channel cross section consist of a somewhat vertical bank, a slope, and a more-or-less level substrate. Channels in Netarts Bay are either tidal where bay water flows in and out with the tides, or they are drainage channels that formed largely by freshwater runoff that cuts through soil substrates with low resistance or weakly stabilizing vegetation. Tidal channels, including those that are mainstream, are fairly wide and deep and may not empty completely during low tides. Drainage channels, such as blind dendritic and subsidiary channels, are usually higher in elevation, and often narrow down to a few inches across near their blind ends. They flood with bay water only at the highest tides. Some of these blind channel extend to the perimeter of the marsh and to the edge of the forest. They may also tunnel under the marsh surface where overlying vegetation is thick and stable. It has been noted in other marshes that even the smallest channels, some only a few inches wide and deep, can influence plant distributions (Sanderson et. al., 2000).

Most channels meander in a sinuous, snake-like pattern. This meandering is the result of ebbs and floods of tidal waters that cause the slumping of channel banks, particularly during at ebb flows which, according to Fagherazzi et. al., 2004, have water velocities stronger that those during flood flows, resulting in differential bank erosion.