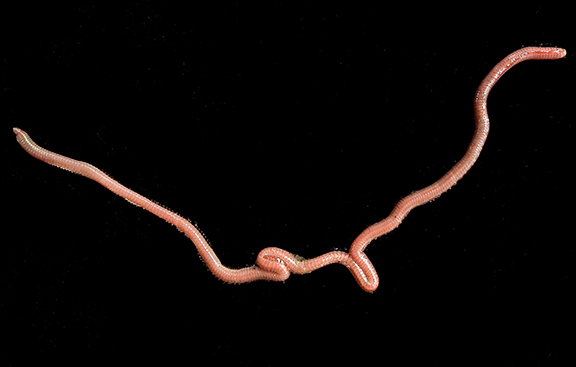

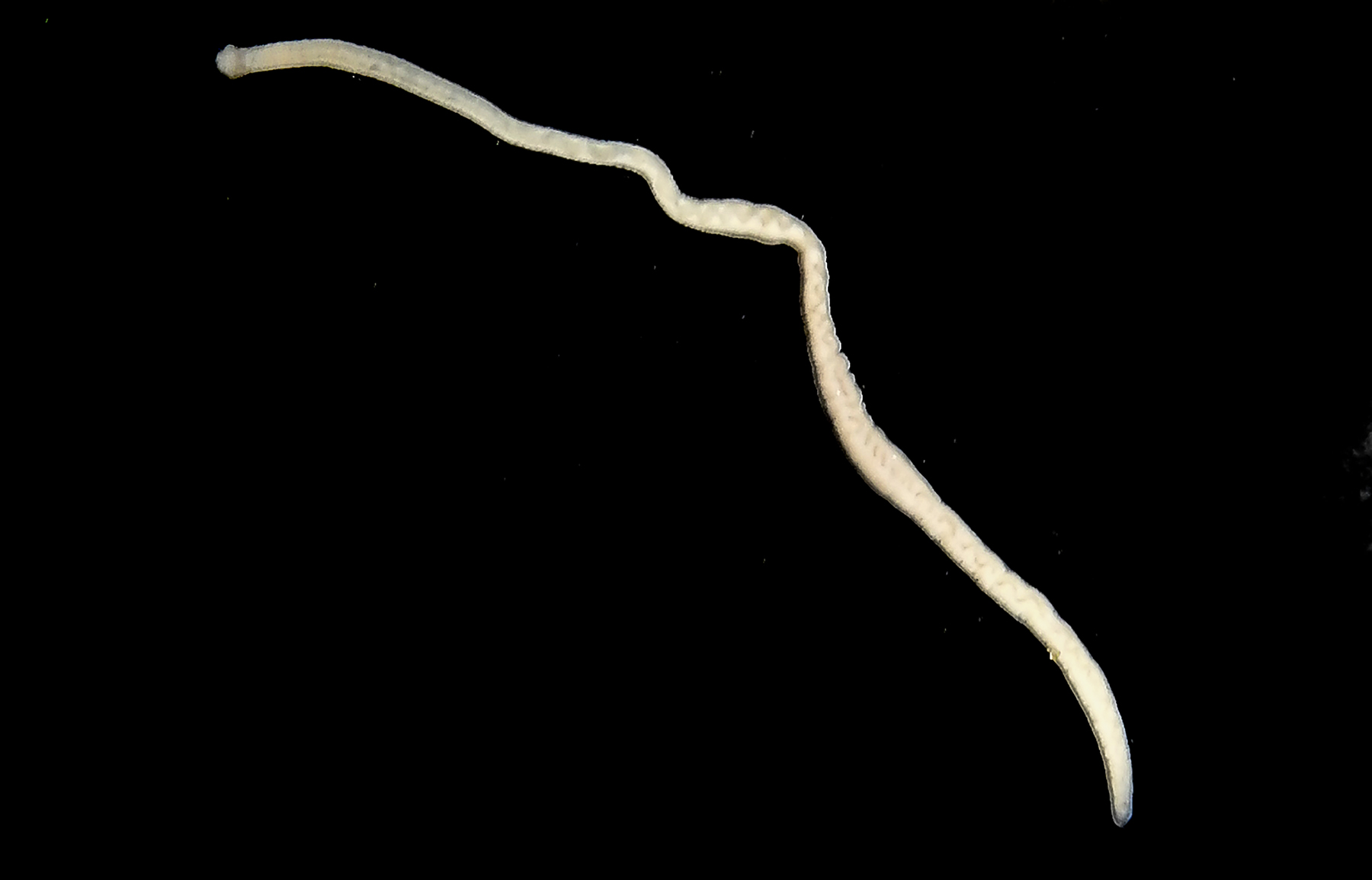

Phascolosoma agassizi

Peanut Worm

Alaska to Mexico

Familiy Phasoclosomatidae

Native

The Peanut Worm, Phascolosoma agassizi, was historically placed in the phylum Sipuncula, separate from the Annelids because it is unsegmented. Recent phylogenetic evidence has now placed them in the phylum Annelida, which suggests that segments and chaetae, characteristic of Annelids, were evolutionarily lost in these worms. The Sipuncula, now a clade, consists of about 150 species. They have round sausage-shaped bodies divided into a thick trunk and an extendable neck-like, anterior “introvert” that can be retracted into the trunk by introversion (folding in on itself). The mouth is on the end of the introvert and surrounded by small ciliated tentacles. The epidermis of P. agassizi is brownish with dark spots on the trunk and transverse streaks on the neck and is covered with glandular papillae. In Netarts Bay, it can be found in gravel areas, under rocks and cobbles, often in burrows. It feeds on organic detritus.